Preperation Before Class

apue 编程环境搭建

Figure 1.3 List all the files in a directory

1 |

|

这里简单说一下 apue 的编程环境搭建,实际上只需要用到一点点make、环境变量和gcc 命令的知识。

选择 2013 年出版的 apue3,然后点击 source code,然后根据提示点击 here 下载。

拿到编程环境的源码之后,解压进入目录,使用 make 命令编译得到 libapue.a,这是个静态库,生成在 lib 目录下。然后将 include 目录下的 apue.h 这个头文件和 libapue.a 这个静态库分别放置在/usr/include/和/usr/local/lib/下面(这两个路径就是写入环境变量的路径,gcc 命令会在编译的时候搜寻这两个路径)。

然后使用gcc -o main.o main.c -lapue编译得到 main.o,因为上一步我们将 apue.h 和 libapue.a 放入了环境变量路径下面,所以我们使用它们的时候都不用再指明其路径了。

然后运行 main.o:./main.o .,将当前目录下的所有文件名打印出来。

如果编译失败,使用 make clean 可以清空编译结果,然后就可以使用 make 重新编译了。不要将程序命名为.cpp 文件,这样的话即便你使用 gcc 编译 myls.cpp,也会出错,更不要使用 g++去编译 myls.cpp,因为库是用 gcc 编译的。

When the program is done, it calls the function exit with an argument of 0. The function exit terminates a program. By convention, an argument of 0 means OK, and an argument between 1 and 255 means that an error occurred.

man 命令

man 命令是 unix 系统中的一个非常重要的命令,它提供了所有命令的详细的使用方法。

Historically, UNIX systems lumped all eight sections together into what was called the UNIX Programmer's Manual. As the page count increased, the trend changed to distributing the sections among separate manuals: one for users, one for programmers, and one for system administrators, for example. Some UNIX systems further divide the manual pages within a given section, using an uppercase letter. For example, all the standard input/output (I/O) functions in AT&T [1990e] are indicated as being in Section 3S, as in fopen(3S). Other systems have replaced the numeric sections with alphabetic ones, such as C for commands.

Unix Architecture

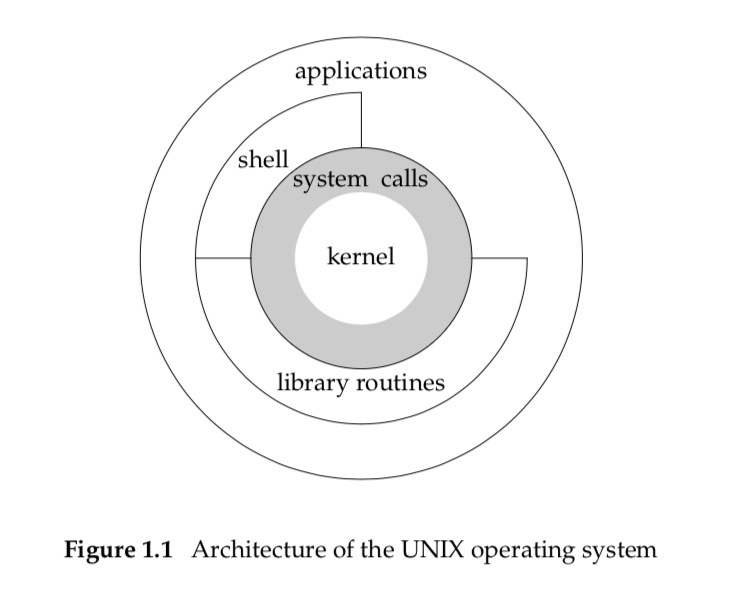

下图清晰的描述了 Unix 的架构:

图中最重要的两个概念是:内核和系统调用,下面是对这两个概念的简单介绍:

- kernel: In a strict sense, an operating system can be defined as the software that controls the hardware resources of the computer and provides an environment under which programs can run.

- system calls: The interface to the kernel is a layer of software called the system calls .

Shell

A shell is a command-line interpreter that reads user input and executes commands. The user input to a shell is normally from the terminal (an interactive shell) or sometimes from a file (called a shell script).

The system knows which shell to execute for us based on the final field in our entry in the password file.

bash: The Bourne-again shell is the GNU shell provided with all Linux systems. It was designed to be POSIX conformant, while still remaining compatible with the Bourne shell. It supports features from both the C shell and the Korn shell.

Files and Directories

文件系统是 Unix 系统中一个非常重要的部分,里面有许多很重要的设计。文件系统从逻辑层面上看是一个树状结构,所有文件和目录都从属于一个根目录。

- root: Everything starts in the directory called root, whose name is the single character

/. - directory: A directory is a file that contains directory entries. Logically, we can think of each directory entry as containing a filename along with a structure of information describing the attributes of the file. The attributes of a file are such things as the type of file (regular file, directory), the size of the file, the owner of the file, permissions for the file (whether other users may access this file), and when the file was last modified.

We make a distinction between the logical view of a directory entry and the way it is actually stored on disk. Most implementations of UNIX file systems don't store attributes in the directory entries themselves, because of the difficulty of keeping them in synch when a file has multiple hard links.

文件名和路径名这里面也有讲究:

- 文件名中不能包含斜杠和空字符: The only two characters that cannot appear in a filename are the slash character (/) and the null character. The slash separates the filenames that form a pathname (described next) and the null character terminates a pathname.

- dot 和 dot-dot: Two filenames are automatically created whenever a new directory is created: . (called dot) and .. (called dot-dot). Dot refers to the current directory, and dot-dot refers to the parent directory. In the root directory, dot-dot is the same as dot.

- 相对路径和绝对路径: A sequence of one or more filenames, separated by slashes and optionally starting with a slash, forms a pathname. A pathname that begins with a slash is called an absolute pathname; otherwise, it's called a relative pathname. Relative pathnames refer to files relative to the current directory.

我们不知道形如:

/usr/local/lib/hello的路径中 hello 是目录还是普通文件,哈哈,我觉得 unix 当初在设计上应该强制目录必须以斜杠结尾。

还有两个比较特殊的目录:

- working directory: Every process has a working directory, sometimes called the current working directory. This is the directory from which all relative pathnames are interpreted. A process can change its working directory with the chdir function.

- home directory: When we log in, the working directory is set to our home directory. Our home directory is obtained from our entry in the password file.

File Descriptors

file descriptor: File descriptors are normally small non-negative integers that the kernel uses to identify the files accessed by a process. Whenever it opens an existing file or creates a new file, the kernel returns a file descriptor that we use when we want to read or write the file.

Standard Input, Standard Output, and Standard Error: By convention, all shells open three descriptors whenever a new program is run: standard input, standard output, and standard error. If nothing special is done, as in the simple command

1 | ls |

then all three are connected to the terminal. Most shells provide a way to redirect any or all of these three descriptors to any file. For example,

1 | ls > file.list |

executes the ls command with its standard output redirected to the file named file.list.

stdin 的文件描述符是 0,stdout 的文件描述符是 1,stderr 的文件描述符是 2。all three are connected to the terminal,此 terminal 非彼 terminal,这里指的是硬件终端,stdin 的默认输入对象是 keyboard,stdout 和 stderr 的默认输出对象是 screen。

Redirection

To redirect a file descriptor, we use N>, where N is a file descriptor. If there's no file descriptor, then stdout is used, like in echo hello > new-file.

将 stderr 重定向到文件:

1 | command1 2> error.log |

将 stderr 重定向到 stdout:

1 | command-name 2>&1 |

将 stdout 和 stderr 都重定向到文件:

1 | command-name &>file |

或者这么写:

1 | command > file-name 2>&1 |

不能调换顺序:command 2>&1 > file-name,这样写就错了。

The wrong version points stderr at stdout (which outputs to the shell), then redirects stdout to the file. Thus only stdout is pointing at the file, because stderr is pointing to the “old” stdout.

Figure 1.4 Copy standard input to standard output

1 |

|

The <unistd.h> header, included by apue.h, and the two constants STDIN_FILENO and STDOUT_FILENO are part of the POSIX standard (about which we’ll have a lot more to say in the next chapter). This header contains function prototypes for many of the UNIX system services, such as the read and write functions that we call.

The constants STDIN_FILENO and STDOUT_FILENO are defined in <unistd.h> and specify the file descriptors for standard input and standard output.

The read function returns the number of bytes that are read, and this value is used as the number of bytes to write. When the end of the input file is encountered, read returns 0 and the program stops. If a read error occurs, read returns −1. Most of the system functions return −1 when an error occurs.

If we compile the program into the standard name (a.out) and execute it as

1 | ./a.out > data |

standard input is the terminal, standard output is redirected to the file data, and standard error is also the terminal. If this output file doesn’t exist, the shell creates it by default. The program copies lines that we type to the standard output until we type the end-of-file character (usually Control-D).

The notation ˆD is used to indicate a control character. Control characters are special characters formed by holding down the control key—often labeled Control or Ctrl—on your keyboard and then pressing another key at the same time. Control-D, or ˆD, is the default end-of-file character.

If we run

1 | ./a.out < infile > outfile |

then the file named infile will be copied to the file named outfile.

The standard I/O functions provide a buffered interface to the unbuffered I/O functions. Using standard I/O relieves us from having to choose optimal buffer sizes, such as the BUFFSIZE constant in Figure 1.4. The standard I/O functions also simplify dealing with lines of input (a common occurrence in UNIX applications). The fgets function, for example, reads an entire line. The read function, in contrast, reads a specified number of bytes.

The most common standard I/O function is printf. In programs that call printf, we’ll always include <stdio.h> as this header contains the function prototypes for all the standard I/O functions.

Figure 1.5 Copy standard input to standard output, using standard I/O

1 |

|

The function getc reads one character at a time, and this character is written by putc. After the last byte of input has been read, getc returns the constant EOF (defined in <stdio.h>). The standard I/O constants stdin and stdout are also defined in the <stdio.h> header and refer to the standard input and standard output.

Programs and Processes

program: A program is an executable file residing on disk in a directory. A program is read into memory and is executed by the kernel as a result of one of the seven exec functions.

process: An executing instance of a program is called a process, a term used on almost every page of this text. Some operating systems use the term task to refer to a program that is being executed.

The UNIX System guarantees that every process has a unique numeric identifier called the process ID. The process ID is always a non-negative integer.

Figure 1.6 Print the process ID

1 |

|

输出结果:

1 | ➜ apue.3e ./fig1.6 |

Process Control

There are three primary functions for process control: fork, exec, and waitpid. (The exec function has seven variants, but we often refer to them collectively as simply the exec function.)

Figure 1.7 Read commands from standard input and execute them

1 |

|

There are several features to consider in this 30-line program.

- We use the standard I/O function fgets to read one line at a time from the standard input. When we type the end-of-file character (which is often Control-D) as the first character of a line, fgets returns a null pointer, the loop stops, and the process terminates.

- Because each line returned by fgets is terminated with a newline character, followed by a null byte, we use the standard C function strlen to calculate the length of the string, and then replace the newline with a null byte. We do this because the execlp function wants a null-terminated argument, not a newline-terminated argument.

- We call

forkto create a new process, which is a copy of the caller. We say that the caller is the parent and that the newly created process is the child. Thenforkreturns the non-negative process ID of the new child process to the parent, and returns 0 to the child. Because fork creates a new process, we say that it is called once—by the parent—but returns twice—in the parent and in the child. - In the child, we call execlp to execute the command that was read from the standard input. This replaces the child process with the new program file. The combination of fork followed by exec is called spawning a new process on some operating systems. In the UNIX System, the two parts are separated into individual functions

- Because the child calls execlp to execute the new program file, the parent wants to wait for the child to terminate. This is done by calling

waitpid, specifying which process to wait for: the pid argument, which is the process ID of the child. The waitpid function also returns the termination status of the child—the status variable—but in this simple program, we don’t do anything with this value. We could examine it to determine how the child terminated. - The most fundamental limitation of this program is that we can't pass arguments to the command we execute. We can't, for example, specify the name of a directory to list. We can execute ls only on the working directory. To allow arguments would require that we parse the input line, separating the arguments by some convention, probably spaces or tabs, and then pass each argument as a separate parameter to the execlp function. Nevertheless, this program is still a useful demonstration of the UNIX System's process control functions.

If we run this program, we get the following result. Note that our program has a different prompt—the percent sign—to distinguish it from the shell's prompt.

1 | $ ./fig1.7 |

Threads

All threads within a process share the same address space, file descriptors, stacks, and process-related attributes. Each thread executes on its own stack, although any thread can access the stacks of other threads in the same process. Because they can access the same memory, the threads need to synchronize access to shared data among themselves to avoid inconsistencies.

Like processes, threads are identified by IDs. Thread IDs, however, are local to a process. A thread ID from one process has no meaning in another process. We use thread IDs to refer to specific threads as we manipulate the threads within a process.

threads were added to the UNIX System long after the process model was established

Error Handling

When an error occurs in one of the UNIX System functions, a negative value is often returned, and the integer errno is usually set to a value that tells why. For example, the open function returns either a non-negative file descriptor if all is OK or −1 if an error occurs. An error from open has about 15 possible errno values, such as file doesn’t exist, permission problem, and so on. Some functions use a convention other than returning a negative value. For example, most functions that return a pointer to an object return a null pointer to indicate an error.

The file <errno.h> defines the symbol errno and constants for each value that errno can assume. Each of these constants begins with the character E. Also, the first page of Section 2 of the UNIX system manuals, named intro(2), usually lists all these error constants. For example, if errno is equal to the constant EACCES, this indicates a permission problem, such as insufficient permission to open the requested file.

On Linux, the error constants are listed in the errno(3) manual page.

POSIX and ISO C define errno as a symbol expanding into a modifiable lvalue of type integer. This can be either an integer that contains the error number or a function that returns a pointer to the error number. The historical definition is

1 | extern int errno; |

But in an environment that supports threads, the process address space is shared among multiple threads, and each thread needs its own local copy of errno to prevent one thread from interfering with another. Linux, for example, supports multithreaded access to errno by defining it as

1 | extern int *__errno_location(void); |

There are two rules to be aware of with respect to errno. First, its value is never cleared by a routine if an error does not occur. Therefore, we should examine its value only when the return value from a function indicates that an error occurred. Second, the value of errno is never set to 0 by any of the functions, and none of the constants defined in <errno.h> has a value of 0.

Two functions are defined by the C standard to help with printing error messages.

1 |

|

This function maps errnum, which is typically the errno value, into an error message string and returns a pointer to the string.

The perror function produces an error message on the standard error, based on the current value of errno, and returns.

1 |

|

It outputs the string pointed to by msg, followed by a colon and a space, followed by the error message corresponding to the value of errno, followed by a newline.

Figure 1.8 Demonstrate strerror and perror

1 |

|

输出结果:

1 | $ ./fig1.8 |

argv[0] 表示输入的第一个参数,也就是命令名

Error Recovery

The errors defined in <errno.h> can be divided into two categories: fatal and nonfatal. A fatal error has no recovery action. The best we can do is print an error message on the user's screen or to a log file, and then exit. Nonfatal errors, on the other hand, can sometimes be dealt with more robustly. Most nonfatal errors are temporary, such as a resource shortage, and might not occur when there is less activity on the system.

Resource-related nonfatal errors include EAGAIN, ENFILE, ENOBUFS, ENOLCK, ENOSPC, EWOULDBLOCK, and sometimes ENOMEM. EBUSY can be treated as nonfatal when it indicates that a shared resource is in use. Sometimes, EINTR can be treated as a nonfatal error when it interrupts a slow system call.

The typical recovery action for a resource-related nonfatal error is to delay and retry later. This technique can be applied in other circumstances. For example, if an error indicates that a network connection is no longer functioning, it might be possible for the application to delay a short time and then reestablish the connection. Some applications use an exponential backoff algorithm, waiting a longer period of time in each subsequent iteration.

User Identification

Password File

/etc/passwd: When we log in to a UNIX system, we enter our login name, followed by our password. The system then looks up our login name in its password file, usually the file /etc/passwd. If we look at our entry in the password file, we see that it's composed of seven colon-separated fields: the login name, encrypted password, numeric user ID (205), numeric group ID (105), a comment field, home directory (/home/sar), and shell program (/bin/ksh).

密码文件的条目的格式如下:

1 | 登录名:加密过的密码:user ID:group ID:注解:home目录:shell |

All contemporary systems have moved the encrypted password to a different file.

1 | sar:x:205:105:Stephen Rago:/home/sar:/bin/ksh |

我们可以看到这个文件很关键,因为他配置了我们的很多信息,比如 home 目录,默认的 shell。

User ID

The user ID from our entry in the password file is a numeric value that identifies us to the system. This user ID is assigned by the system administrator when our login name is assigned, and we cannot change it. The user ID is normally assigned to be unique for every user. We'll see how the kernel uses the user ID to check whether we have the appropriate permissions to perform certain operations.

We call the user whose user ID is 0 either root or the superuser. The entry in the password file normally has a login name of root, and we refer to the special privileges of this user as superuser privileges. As we'll see in Chapter 4, if a process has superuser privileges, most file permission checks are bypassed. Some operating system functions are restricted to the superuser. The superuser has free rein over the system.

Client versions of Mac OS X ship with the superuser account disabled; server versions ship with the account already enabled. Instructions are available on Apple’s Web site describing how to enable it. See http://support.apple.com/kb/HT1528.

Group ID

Our entry in the password file also specifies our numeric group ID. This, too, is assigned by the system administrator when our login name is assigned. Typically, the password file contains multiple entries that specify the same group ID. Groups are normally used to collect users together into projects or departments. This allows the sharing of resources, such as files, among members of the same group. We’ll see in Section 4.5 that we can set the permissions on a file so that all members of a group can access the file, whereas others outside the group cannot.

There is also a group file that maps group names into numeric group IDs. The group file is usually /etc/group.

为何使用数字型 ID,主要原因如下:

The use of numeric user IDs and numeric group IDs for permissions is historical. With every file on disk, the file system stores both the user ID and the group ID of a file’s owner. Storing both of these values requires only four bytes, assuming that each is stored as a two-byte integer. If the full ASCII login name and group name were used instead, additional disk space would be required. In addition, comparing strings during permission checks is more expensive than comparing integers.

Users, however, work better with names than with numbers, so the password file maintains the mapping between login names and user IDs, and the group file provides the mapping between group names and group IDs. The ls -l command, for example, prints the login name of the owner of a file, using the password file to map the numeric user ID into the corresponding login name.

Early UNIX systems used 16-bit integers to represent user and group IDs. Contemporary UNIX systems use 32-bit integers.

Figure 1.9 Print user ID and group ID

1 |

|

Supplementary Group IDs

supplementary group:In addition to the group ID specified in the password file for a login name, most versions of the UNIX System allow a user to belong to other groups. This practice started with 4.2BSD, which allowed a user to belong to up to 16 additional groups. These supplementary group IDs are obtained at login time by reading the file /etc/group and finding the first 16 entries that list the user as a member. As we shall see in the next chapter, POSIX requires that a system support at least 8 supplementary groups per process, but most systems support at least 16.

/etc/group格式如下:

1 | _analyticsusers:*:250:_analyticsd,_networkd,_timed |

解释:

1 | 组名:口令:组ID:组内用户列表 |

Signal

Signals are a technique used to notify a process that some condition has occurred. For example, if a process divides by zero, the signal whose name is SIGFPE (floating-point exception) is sent to the process. The process has three choices for dealing with the signal.

- Ignore the signal. This option isn't recommended for signals that denote a hardware exception, such as dividing by zero or referencing memory outside the address space of the process, as the results are undefined.

- Let the default action occur. For a divide-by-zero condition, the default is to terminate the process.

- Provide a function that is called when the signal occurs (this is called “catching” the signal). By providing a function of our own, we'll know when the signal occurs and we can handle it as we wish.

Many conditions generate signals. Two terminal keys, called the interrupt key—often the DELETE key or Control-C—and the quit key—often Control-backslash—are used to interrupt the currently running process. Another way to generate a signal is by calling the kill function. We can call this function from a process to send a signal to another process. Naturally, there are limitations: we have to be the owner of the other process (or the superuser) to be able to send it a signal.

Figure 1.10 Read commands from standard input and execute them

1 |

|

这段代码使用自己定义的sig_int函数捕获 SIGINT 信号,但如果你按^C,代码依然会结束。原因是^C 也能像^D 一样让fgets函数返回一个 NULL。另外就算 while 是个死循环:

1 | while(1){ |

当你按第二次^C 的时候,程序依然会退出,这就说明这个signal(SIGINT, sig_int)是一次性的。然后我将其写在了循环中,

1 | while (1) { |

无论你按多少次^C 都无法退出了,另外还有一个现象,每次按^C开始休眠一秒钟...会立马打印出来。

Time Values

Historically, UNIX systems have maintained two different time values:

Calendar time. This value counts the number of seconds since the Epoch: 00:00:00 January 1, 1970,Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). (Older manuals refer to UTC as Greenwich Mean Time.) These time values are used to record the time when a file was last modified, for example.

The primitive system data type

time_tholds these time values.Process time. This is also called CPU time and measures the central processor resources used by a process. Process time is measured in clock ticks, which have historically been 50, 60, or 100 ticks per second.

The primitive system data type

clock_tholds these time values. (We’ll show how to obtain the number of clock ticks per second with thesysconffunction in Section 2.5.4.)

有两种类型的时间:日历时间和进程时间,日历时间也就是 UTC。

When we measure the execution time of a process, as in Section 3.9, we’ll see that the UNIX System maintains three values for a process:

- Clock time

- User CPU time

- System CPU time

The clock time, sometimes called wall clock time, is the amount of time the process takes to run, and its value depends on the number of other processes being run on the system. Whenever we report the clock time, the measurements are made with no other activities on the system.

The user CPU time is the CPU time attributed to user instructions. The system CPU time is the CPU time attributed to the kernel when it executes on behalf of the process. For example, whenever a process executes a system service, such as read or write, the time spent within the kernel performing that system service is charged to the process. The sum of user CPU time and system CPU time is often called the CPU time.

度量进程执行时间,有三种:

- 墙上时钟,也就是进程执行花费的总时间。

- 用户 CPU 时间,是用户模式(非内核)下的 CPU 使用时间

- 系统 CPU 时间,是进程进入内核执行的 CPU 使用时间

It is easy to measure the clock time, user time, and system time of any process: simply execute the time(1) command, with the argument to the time command being the command we want to measure. For example:

1 | cd /usr/include |

结果:

1 | real 0m0.81s |

The output format from the time command depends on the shell being used, because some shells don’t run /usr/bin/time, but instead have a separate built-in function to measure the time it takes commands to run. time 命令的输出格式取决于使用什么 shell,因为有些 shell 并不运行:/usr/bin/time,而是运行自己内置的一个 time 函数。